Kunstenaars collectief Zuiderlink – Project Deur in mijn hoofd, Laagstraat 50 Tilburg

Een groep kunstenaars uit omgeving Eindhoven, Tilburg en Dordrecht bundelt haar krachten en creëert na een unieke werkperiode van zes weken een expositie in een leegstaand woonhuis in Tilburg.

A group of artists from the Eindhoven, Tilburg and Dordrecht areas join forces to create an exhibition in an empty house in Tilburg after a unique six-week working period.

Deelnemende kunstenaars/ participating artists:

Anouk Bax | Bram van Helden | Eva Hoonhout | Geertje Kapteijns | Jeroen Offerman | Gijs Pape | Manuela Porceddu | Lilia Scheerder | Marjan Wester

Het project is gecureerd door/ the project is curated by: Linda Köke en Jorne Vriens

Het project is gesponsord door Tiwos Tilburgse woonstichting en Cultuur Eindhoven

Kunstexpositie in een Tilburgs woonhuis

Een woning scheidt het private leven van publieke activiteit. Al een miljoen jaar geleden hield de Homo Erectus zich staande in een complexe wereld van sociale structuren die georganiseerde jachtpartijen met zich meebrachten. Op gezette tijden trok hij zich daarom terug naar een vaste standplaats. Netflix bestond niet; Home Erectus hield zich daarentegen bezig met de beheersing van het kampvuur. Communicatieve vaardigheden waren op zulk niveau dat de enige sociale activiteit die ‘s avonds plaatsvond het grooming-ritueel op het haardkleed was.

De Homo Erectus stond bekend als begenadigd kunstenaar. Omdat spreektaal nog niet voorhanden was, werden verhalen verteld door een afdruk achter te laten in de ruimtes die als schuilplaats dienden. “Hoe verhoud ik mij tot deze ruimte waar ik gewens ben?” was een vraag die zich opwierp wanneer de kunstenaar aanving met zijn creatie. “Ga ik reageren op de geschiedenis van mijn woonplek of stap ik er blanco in? Moet ik deze grot bezien als White Cube of juist als airBnB?”

Dilemma’s als “Zijn mijn huisgenoten te vertrouwen?”, “Zet ik koffie voor de buren of sluit ik de rolluiken tegen roofdieren?”, “Moet mijn collectie ontsloten worden voor publiek en wat heeft dat voor impact op de waarde van mijn bezit?” waren van meer praktische aard en hadden betrekking op de verhouding tot de buitenwereld.

Tien kunstenaars en twee curatoren kruipen in de huid van een leegstaande doorzon-woning om met elkaar aan het werk te gaan in het centrum van Tilburg. Deze huisgenoten begeleiden elkaar tijdens het ontwikkelproces om de gedachten scherp te houden en elkanders werk onder de loep te leggen. Is het waardevol om de deuren naar elkaar te openen en naar een groter publiek? Wij hangen het toutje uit de brievenbus. Na zes weken volgt een expositie en ontsluiten wij de poort.

Tekst door kunstenaars collectief Zuiderlink, 2019

Art exhibition in a Tilburg residence

A home separates private life from public activity. A million years ago, Homo Erectus was already holding his own in a complex world of social structures that involved organised hunting parties. At regular intervals he retreated to a fixed location. Netflix did not exist; Home Erectus, on the other hand, was concerned with mastering the campfire. Communication skills were such that the only social activity that took place at night was the grooming ritual on floor close to the hearth.

Homo Erectus was known as a gifted artist. Since spoken language was not yet available, stories were told by leaving an imprint in the spaces that served as hiding places. “How do I relate to this space where I am living?” was a question that arose when the artist started his creation. “Am I going to react to the history of my place of residence or enter it blankly? Should I view this cave as a White Cube or as an airBnB?”

Dilemmas such as “Can my housemates be trusted?”, “Do I make coffee for the neighbours or do I close the shutters against predators?”, “Should my collection be opened to the public and what impact will that have on the value of my property?” were of a more practical nature and concerned the relationship to the outside world.

Ten artists and two curators have inhabited an empty house to start working together in the centre of Tilburg. These housemates accompany each other during the development process to keep their minds sharp and put each other’s work under the microscope. Is it valuable to open the doors to each other and to a larger audience? We hang it out to dry. After six weeks, there will be an exhibition and we will open the gate.

Text by artists collective Zuiderlink, 2019

Van links naar rechts: Manuela Porceddu, Eva Hoonhout, Geertje Kapteijns, Antoine Panaché, Jeroen Offerman, Anouk Bax, Marjan Wester en Bram van Helden

Zo’n vijftig jaar geleden werd huisnummer 50 gebouwd in de Laagstraat. Details zoals de oranjebruine tegels laten een jaren 70 smaak zien. Kijk naar de slijtplekken in de vloer en je ziet dat hier geleefd is. Vooral de afgelopen jaren heeft het huis veel bewoners gehad. Nu is het de beurt geweest aan kunstenaars om zich de kamers, keukens en tuin eigen te maken. De werken die je tegenkomt zijn veelal gemaakt in de ruimte waar ze nu zijn tentoongesteld. Te gast zijn betekent hier dat alle deuren open mogen worden getrokken.

Tekst door Jorne Vriens

About 50 years ago house number 50 was built in the Laagstraat. Details such as the orange-brown tiles show a 70s flavour. Look at the wear and tear in the floor and you can see that people have lived here. The house has had many occupants, especially in recent years. Now it has been the turn of artists to make the rooms, kitchens and garden their own. The works that you will come across were mostly created in the room where they are now exhibited. Being a guest here means that all doors may be opened.

Text by Jorne Vriens

Een van de vorige bewoners zat vaak in de vensterbank van zijn gedeelde slaapkamer, zo werd aan Anouk Bax verteld. Even onverstoorbaar als de takken die nu zijn plek innemen, zat hij daar te roken. De grijze vloer en het behang dat voorzichtig van de muur is gescheurd, hebben de kamer ingrijpend veranderd. Wat is er nodig om je ergens thuis te voelen? De hutten in de tuin zijn de meest primitieve vorm van een ‘thuis’. Een eigen kamer, of alleen maar een mooi behang volstaat misschien al.

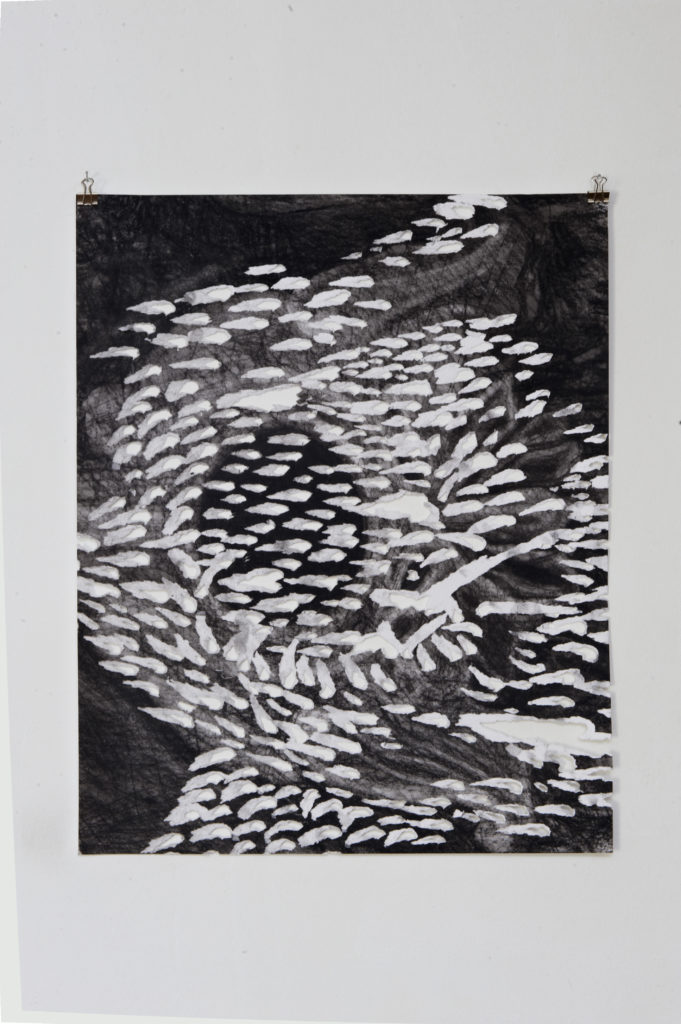

Geertje Kapteijns bracht verf dun aan op papier, waardoor die op sommige plekken is uitgelopen. Door het knippen en plakken van stukken papier is alleen te zien dat het om portretten gaat, zonder dat te herkennen is wie geportretteerd is. Net als bij een vervagende herinnering moet je zelf aan de slag om het beeld weer helder te krijgen.

Wanneer de wereld verkleind zou worden, is er makkelijker mee te spelen. Neem een poppenhuis waar de grotemensenwereld in miniatuurformaat een speeltuin wordt. Marjan Wester en Gijs Pape presenteren een wereld op schaal in hun kijkdoos. Hierin is ruimte voor een soort filmset en even verderop een hoekig houten sculptuur. Het zicht op de Tilburgse skyline dat je van de voor- en achterkant van het huis hebt, is aaneengeplakt. Een kwestie van spelen.

Een robot is een onvermoeibare werker. Als krachtig apparaat dat nooit om een pauze vraagt, heeft het de productie goedkoper en sneller gemaakt. Eva Hoonhout maakte een monument voor de robotarm. De efficiëntie van de arm staat in groot contrast met het bankje waar een Japanse theeceremonie zou kunnen plaatsvinden, een ritueel waar aandacht veel belangrijker is dan een resultaat. Want wat doen we met de tijd die we door automatisering en andere vormen van efficiëntie winnen?

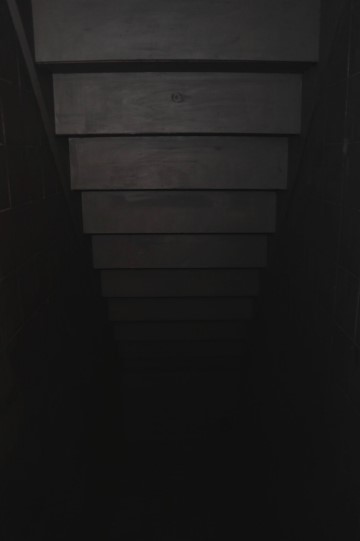

Nog voordat de betekenis van de werken van Jeroen Offerman duidelijk wordt, doen ze al wel iets. Het harde licht van de tl-buizen kan het best van een afstandje bekeken worden en de volledig zwarte trapkast kan makkelijk een angst oproep voor het donker. Wat ook sneller gaat dan het denken is de manier waarop vriendschap wordt gesloten in sociale netwerken. Wanneer een vriendschapsverzoek is geaccepteerd verschijnt ‘jullie zijn nu vrienden’. Ook hier geldt dat die vriendschap er allang was voordat die ook online bestond.

Prachtige details van de verder doodnormale woonwijk zijn door Manuela Porceddu met een camera vastgelegd. het levert rustgevende beelden op. Zolang je maar goed kijkt valt overal iets moois te zien, lijkt de kunstenaar te zeggen. De omgeving van het huis is geprojecteerd op de glimmende tegels in de bijkeuken. Met die aandacht kan een gevonden voorwerp grote indruk maken, die in dit geval een afdruk oplevert van de patronen van de verschillende tegeltjes in het huis.

Denk aan wegwerpmateriaal en je denkt vast aan plastic. Ten onrechte, volgens Bram van Helden. Er is zoveel plastic om ons heen dat ook veel langer dan de duur van één mensenleven nodig heeft om door de natuur te worden verwerkt. Bram bedenkt een nieuwe manier om naar plastic te kijken. Een rol tape aan de muur draait hypnotiserende rond. Nog meer leven lijkt er te zitten in een stuk plastic dat bijna als een beestje beweegt. Plastic krijgt zo de status van een materiaal waar we mee samen moeten leven.

In de badkamer spoel je de dag of nacht weg en maak je het schoongeboend lichaam klaar voor wat komen gaat. Het is een plek van transformatie, wat Lilia Scheerder met haar installatie benadrukt. Scheren, opmaken of bijpunten al die badkamerbezigheden maken klaar voor de rol die we spelen. Deze natte cel heeft door de filmachtige schaduwen mogelijk iets onheilspellends. Maar is zo’n decor niet precies wat een acteur nodig heeft om geloofwaardig een emotie over te brengen?

Tekst door Jorne Vriens

One of the previous residents often sat in the windowsill of his shared bedroom, Anouk Bax was told. As imperturbable as the branches that now occupy his place, he sat there smoking. The grey floor and the wallpaper that has been carefully torn off the wall have changed the room dramatically. What does it take to feel at home somewhere? The huts in the garden are the most primitive form of a ‘home’. A room of your own, or just a nice wallpaper, might be enough.

Geertje Kapteijns applied paint thinly on paper, so that it ran out in some places. By cutting and pasting pieces of paper, one can only see that these are portraits, without being able to recognise who has been portrayed. As with a fading memory, you have to work yourself to get the image clear again.

If the world were made smaller, it would be easier to play with it. Take a doll’s house, where the larger-than-life world becomes a miniature playground. Marjan Wester and Gijs Pape present a world on scale in their diorama. In it, there is room for a kind of film set and, a little further on, an angular wooden sculpture. The view of the Tilburg skyline that you have from the front and the back of the house is glued together. A matter of playing.

A robot is a tireless worker. As a powerful device that never asks for a break, it has made production cheaper and faster. Eva Hoonhout made a monument to the robot arm. The efficiency of the arm stands in stark contrast to the bench where a Japanese tea ceremony could take place, a ritual where attention is much more important than a result. For what do we do with the time we gain through automation and other forms of efficiency?

Even before the meaning of Jeroen Offerman’s works becomes clear, they do something. The harsh light of the fluorescent tubes is best viewed from a distance and the completely black staircase cupboard can easily evoke a fear of the dark. Another thing that goes faster than thinking is the way friendships are made in social networks. When a friend request is accepted, the message ‘you are now friends’ appears. Here too, the friendship was there long before it existed online.

Manuela Porceddu used a camera to capture the beautiful details of the otherwise perfectly normal residential area. As long as you look closely, you can see something beautiful everywhere, the artist seems to be saying. The surroundings of the house are projected onto the shiny tiles in the scullery. With that kind of attention, a found object can make a big impression, which in this case is an imprint of the patterns of the different tiles in the house.

Think of disposable material and you probably think of plastic. Wrongly, according to Bram van Helden. There is so much plastic around us that it takes much longer than one human life to be processed by nature. Bram invents a new way of looking at plastic. A roll of tape on the wall spins hypnotically. There seems to be even more life in a piece of plastic that moves almost like an animal. Plastic thus acquires the status of a material we have to live with.

In the bathroom, you wash away the day or night and prepare the cleansed body for what is to come. It is a place of transformation, which Lilia Scheerder emphasises with her installation. Shaving, making up or touching up all those bathroom activities prepare us for the role we play. The filmy shadows of this wet cell may have something ominous about it. But isn’t a setting like this exactly what an actor needs to convincingly convey an emotion?

Text by Jorne Vriens

Het was een lange dag. Ik steek de sleutel in het slot van de voordeur en loop naar binnen. Eerst tijd voor thee. Ik vul de fluitketel en zet hem aan, voordat in mijn favoriete luie stoel in de woonkamer plof. In plaats van de TV hangt hier nu het werk ’16:9’ van Jeroen Offerman, een installatie bestaande uit 5 TL-buizen die prominent op de schoorsteenmantel zijn geplaatst. Het nieuws is er niet op te zien, maar geeft wel de actualiteit weer. Waar we ooit nog gezellig met de familie rond het haardvuur zitten, zitten we nu geïsoleerd rondom de kille lichten van onze smartphones en tablets. De sociale interactie heeft zich van de fysieke wereld naar de digitale wereld verplaatst.

Ik check de waterkoker. Nog niet klaar. Ondertussen check ik even mijn Facebook-tijdlijn terwijl ik de trap oploop. Ik zie een nieuw vriendschapsverzoek en druk op accepteer. Mijn oog valt op de tekst ‘you are now friends’ aan het einde van de gang. We hebben digitale interactie gehad, hoe oppervlakkig dan ook; laten we nu vrienden zijn.

Vermurwd door deze vervreemding en overspoeld door vragen over wie ik in mijn eigen omgeving toelaat, loop ik de tweede kamer in. Hier is het werk van Geertje Kapteijns te zien. Bij eerste betreding van het lege huis was alles leeggehaald, behalve een foto van een voormalige bewoner. Deze foto bracht bij Geertje een verwondering naar boven naar wie hier eerder hebben rondgelopen. Hoe hebben zij het huis tot dat van hen gemaakt? Vanuit deze foto heeft ze met drukinkt een reeks portretten gemaakt die steeds abstracter en anoniemer werden, om uiteindelijk deze individuele prints tot collages te maken.

In de tegenoverliggende kamer vraagt Anouk Bax zich hetzelfde af. Hoe kan een huis bescherming bieden, als een nest? Hoe gaat jouw identiteit ook in de ruimte zitten waar je woont? De kamer was bij binnenkomst voorzien van behang. Anouk gaf de muur en de ruimte een huid, door hierin te scheuren. Geïntrigeerd door het idee van nestelen bracht ze takken de ruimte in, die later ook weer vertakten naar de rest van het huis en zelfs de tuin.

Beneden hoor ik de fluitketel fluiten. Tijd voor thee. Ik loop naar beneden en schenk een kop in, voordat ik weer naar boven loop. In een van de achterste ruimtes heeft Eva Hoonhout een installatie gebouwd die onze relatie met tijd en efficiëntie verbeeldt, met de traditionele Japanse theeceremonie als uitgangspunt. Hier werd uitgebreid de tijd voor genomen, soms zelfs uren. In deze maatschappij moet alles zo efficiënt mogelijk en zo min mogelijk tijd of moeite kosten. Dit wordt in haar installatie verbeeld door de tegenstelling tussen de theeceremonie en de grote robotarmen, zoals die in de auto-industrie te zien zijn. Ik denk aan mijn eigen efficiëntie. Vijf kunstwerken bekeken terwijl de thee staat te koken. Ik neem plaats in Eva’s installatie en blijf er een tijdje zitten, genietend van elke slok.

Tekst door Linda Köke, herfst 2019

It was a long day. I put the key in the lock of the front door and walk in. First, time for tea. I fill the kettle and switch it on, before plopping down in my favourite easy chair in the living room. Instead of the TV, Jeroen Offerman’s work ’16:9′ hangs here now, an installation consisting of five fluorescent tubes that are placed prominently on the mantelpiece. The news is not shown on them, but they do reflect the current events. Where once we sat cosily with the family around the fireplace, we are now isolated around the chilly lights of our smartphones and tablets. Social interaction has moved from the physical world to the digital world.

I check the kettle. It’s not ready yet. Meanwhile, I check my Facebook timeline as I walk up the stairs. I see a new friend request and press accept. I notice the text ‘you are now friends’ at the end of the corridor. We have had digital interaction, however superficial; now we are friends.

Strangled by this alienation and overwhelmed by questions about who I allow into my own environment, I walk into the second room. Here, the work of Geertje Kapteijns is on display. On first entering the empty house, everything had been emptied except for a photograph of a former resident. This photo made Geertje wonder who had lived here before. How did they make the house theirs? From this photo, she used printing ink to make a series of portraits that became increasingly abstract and anonymous, before finally turning these individual prints into collages.

In the opposite room, Anouk Bax asks herself the same question. How can a house offer protection, like a nest? How does your identity become part of the space you live in? The room had wallpaper on entry. Anouk gave the wall and the space a skin, by tearing into it. Intrigued by the idea of nesting, she brought branches into the room, which later branched out into the rest of the house and even the garden.

Downstairs I hear the kettle whistle. Time for tea. I walk downstairs and pour myself a cup, before walking back upstairs. In one of the back rooms, Eva Hoonhout has built an installation that depicts our relationship with time and efficiency, using the traditional Japanese tea ceremony as a starting point. Time was taken extensively for this, sometimes even for hours. In this society, everything has to be as efficient as possible and take as little time or effort as possible. This is represented in her installation by the contrast between the tea ceremony and the large robotic arms, as seen in the car industry. I think of my own efficiency. Five works of art viewed while the tea is boiling. I take a seat in Eva’s installation and stay there for a while, enjoying every sip.

Text by Linda Köke, autumn 2019

Omroep Tilburg maakte twee registraties van onze

aanwezigheid in de Laagstraat 50: